Translate this page into:

Sailing through the COVID-19 challenges on admission rates: An experience-based treatment care model for inpatient psychiatry services from central India

*Corresponding author: Lokesh Kumar Singh, Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India. singhlokesh123@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Godi SM, Singh LK. Sailing through the COVID-19 challenges on admission rates: An experience-based treatment care model for inpatient psychiatry services from central India. Arch Biol Psychiatry. 2024;2:48-52. doi: 10.25259/ABP_27_2023

Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic hit the healthcare system worldwide and led to the imposing of a lockdown in India from March 24, 2020, except for emergency services. All India Institute of Medical Sciences Raipur started the dedicated COVID service facility, and the workforce and logistics were shifted to the new dedicated service. This has impacted the inpatient services provided, including psychiatry services. Hence, we conducted a retrospective record review of inpatient admission during COVID-19, which was compared with the previous year’s admission rates. We also discussed the challenges faced and steps taken to implement and support an experience-based treatment care model for inpatient psychiatry services during the COVID-19 crisis.

Keywords

Coronavirus disease 2019

Psychiatry admissions

Inpatient care

Treatment care model

INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic hit the healthcare system worldwide and led to the imposing of a lockdown in India from the evening of March 24, 2020, except for emergency services.[1] Our hospital started the dedicated COVID service facility, and the workforce and logistics were shifted to the new dedicated service. The routine outpatient department services were shut down on March 25, 2020, in our hospital, but we continued the opioid substitution clinic for opioid-dependent patients.[2] However, the restrictions imposed and fear of uncertainty about the pandemic increased the mental health problems in the general public of India.[3] The lack of access to purchase medications and routine regular follow-ups of patients with mental illness further resulted in exacerbation or relapse of their existing illnesses. Inpatient services were also affected in many parts of the country, but we decided to continue inpatient psychiatric care while exercising COVID-related precautions.[4-6] However, the reason for admission to the inpatient department facility was narrowed down to only those patients requiring care for suicide risk, aggressive behavior, organic etiology, substance use, and catatonia. We further designed a management model to provide psychiatry inpatient services in a general hospital setting during the pandemic.

METHODOLOGY

We did a retrospective chart review of inpatient admissions in the psychiatry ward by comparing admission data during two periods, that is, from April 2019 to March 2020 and from April 2020 to March 2021. Data were collected and analyzed regarding the number of admissions, length of hospital stay, and discharge processes during the COVID-19 pandemic from April 2020 to March 2021. This data was compared with admissions in the previous year to understand the impact of the pandemic on psychiatry inpatient admission rates within a general hospital setting.

Apart from that, we also included the measures and management model adopted by us during the pandemic to ensure smooth functioning. The initial few months were more challenging as our country had restricted facilities for testing. Hence, we tried to adopt the treatment care model based on experience and existing models available universally to provide uninterrupted care.

RESULTS

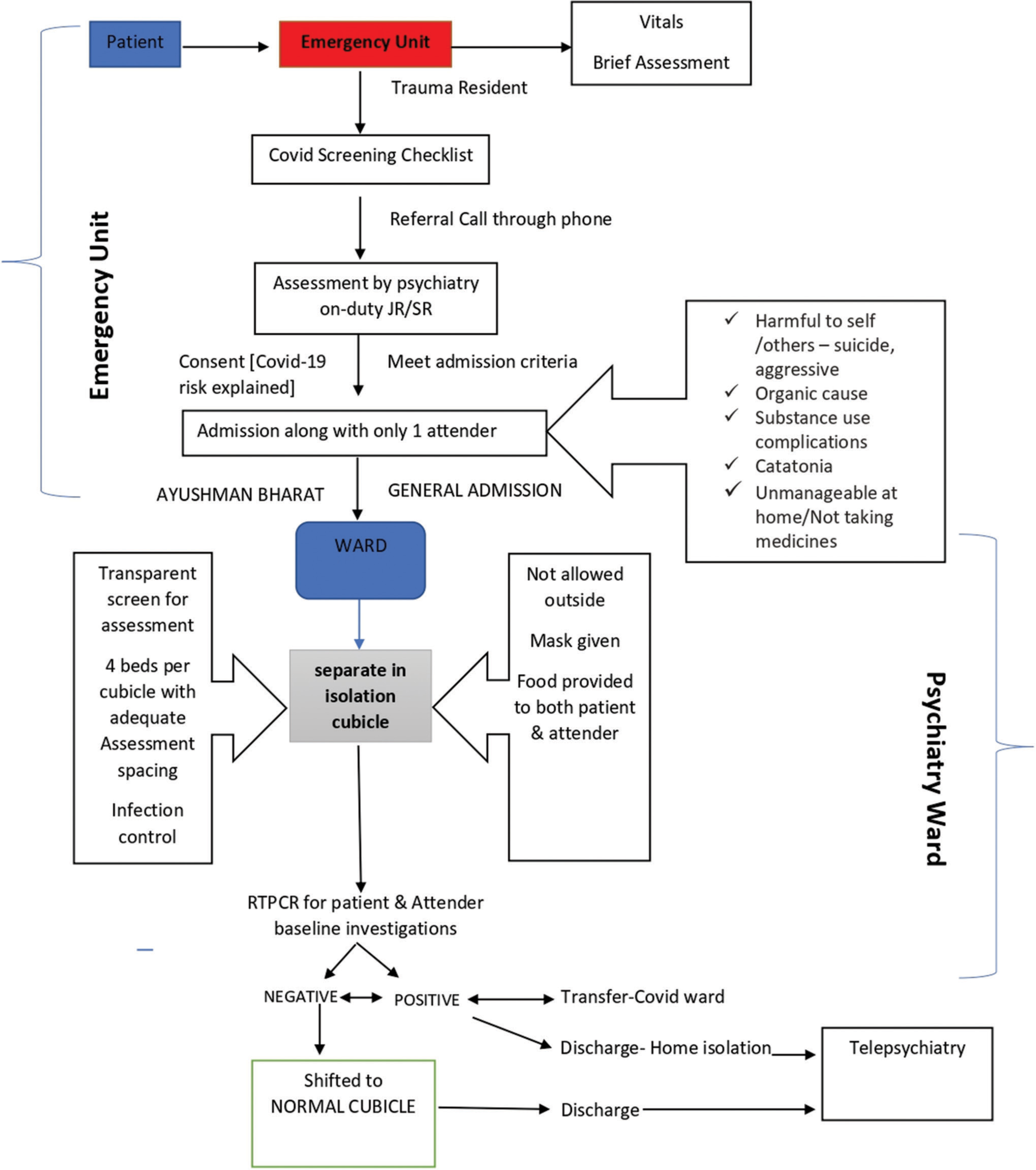

To ensure smooth functioning in the background of COVID-19 challenges and the need for mental health services that require hospitalization, we devised a treatment care model as detailed in the flowchart below [Figure 1]. The psychiatry duty team did an initial assessment to establish the need for hospitalization. The patient, along with their caretaker, was admitted with informed consent after screening using a symptom checklist. This checklist includes the items on basic physical parameters, travel history, and close contact with patients with COVID-19. They were kept in separately assigned isolation cubicles for one week to look for the emergence of COVID-related symptoms, who were later shifted to the wards. Other measures were also taken to control the spread of the virus in the ward. The gap between the beds was increased, daily temperature checks of patients and their caretakers, and daily demonstration of hand hygiene techniques for inpatients was ensured. The infection control measures were followed with regular disinfection of wards, use of N95 masks, and use of personal protective equipment kits by the treating team. During the hospital stay, the movement of the caretaker was also restricted and the length of hospital stay has been curtailed to decrease the exposure and advised follow-up in telepsychiatry at the time of discharge. During the stay in the hospital, if the patient/caretaker developed symptoms and was found COVID-19 positive, the patient/caretaker was either shifted to the COVID isolation ward of our hospital or discharged for home isolation based on the symptom status and patient preference.

- Flow chart showing patient admission and discharge process in psychiatry inpatient ward. RT-PCR: Real-time reverse transcriptasepolymerase chain reaction, JR: Junior resident, SR: Senior resident.

During the COVID pandemic from April 2020 to March 2021, the admission rate, length of stay, and discharge process have been significantly affected. Here, we summarize the inpatient data during the above period to understand the impact of COVID-19 on inpatient care in a psychiatry department in a general hospital setting that was catering to the population of central India, mainly Chhattisgarh and some parts of Orissa and Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra.

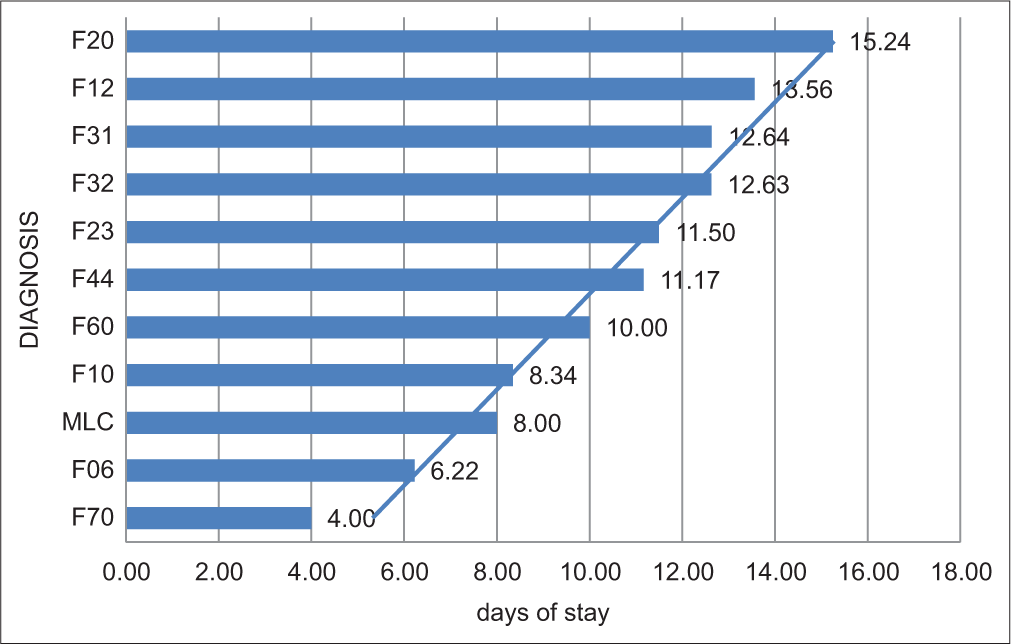

The total number of admissions during this period was 161, compared to 305 admissions between April 2019 and March 2020. There was a 47% reduction in the number of admissions during the time frame of one year during the COVID-19 pandemic in comparison to admissions in the previous year during the corresponding time frame. The most common diagnosis requiring admission was mood disorders, with 33.93% of admissions, followed by psychotic disorders, accounting for 32.74%, and substance use disorders, accounting for 22.62% of total admissions. The average duration of stay in hospital was 12.17 days, with a mean duration of stay low for organic mental disorder (6.2 days), alcohol use disorder (8.34 days), and the longest for psychotic disorders (15.25), as shown in Figure 2. The average duration of stay was 15.54 days, which was comparatively longer for the female gender, while it was 11.16 days for the male gender. The mean duration of stay was also affected by the COVID status of the patient or caretaker, that is, the length of stay was five days when COVID status was positive compared to 13.48 days in non-positive. The COVID positivity rate of inpatients was 11.90%, of which 60% were discharged for home isolation, and 36.6% were transferred out to the COVID ward. In the remaining 3.4% of cases, if the caretaker was positive, then another caretaker in their place was accommodated to continue patient hospitalization. A total of 15 (33%) health personnel from our treating team were also affected by COVID-19 infection during this time. Various team-building measures ensured a healthy work culture during this difficult time, and enthusiastic team members resumed their duties after recovering from COVID-19 infection.

- Number of days of hospital stay according to diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

The pandemic had a significant effect on the admission rate and length of stay of inpatients in our psychiatric department. Comparing the period from April 2020 to March 2021 with the previous year, we observed a 47% reduction in the number of admissions. This decline may be attributed to various factors, including patient reluctance to seek inpatient care during the pandemic and the prioritization of COVID-19 cases over other health concerns by healthcare professionals. The most common disorders that require inpatient management include mood disorders, psychosis will be at higher risk of harm due to the nature of the illness, lack of insight, and poor judgment. Substance use disorders also require inpatient treatment due to complicated withdrawal and distressing symptoms precipitated by sudden unavailability and restrictions on alcohol sales. The ongoing COVID-19 crisis has forced healthcare systems worldwide to adapt and innovate in the face of unprecedented challenges. One such is the experience-based treatment care model employed in inpatient psychiatry services that necessitated us to adopt to continue care. This model focuses on enhancing the overall patient experience while providing mental health care during the pandemic. At the outset, we could have opted for the closure of our inpatient services in the wake of the pandemic, but we chose to run the services for the benefit of patients. Major challenges while running these services were reduced staff-to-patient ratio due to the diversion of staff to COVID duties and health care personnel being affected by COVID-19. Adding to the burden of deficiency in the workforce, managing those patients with predominantly psychotic symptoms with poor insight was a task in the face of rising COVID-positive cases among patients and their caregivers.[7] Patients with mental illness without insight were also the high-risk individuals susceptible to COVID-19 infection as lack of insight may contribute to the difficulties in managing these individuals to adhere to COVID-19 safety measures. This further had a very high chance of nosocomial spread and increased COVID-19 positivity rate in the psychiatry ward compared to other wards.

Gradually, with the availability of test kits and increased COVID positivity rate in psychiatry ward inpatients, we revised our policy to test every patient and their accompanying caretaker admitted to the ward irrespective of symptom or exposure status.[8]

STEPS TAKEN TO SUPPORT THE UNIVERSAL TREATMENT MODEL AT OUR CENTER

Below are some steps taken to address the specific challenges presented by the pandemic at a psychiatric care center to support the universally followed model during COVID-19.

Risk assessment and screening

A comprehensive risk assessment to identify patients who are at higher risk for severe mental health issues due to the pandemic, such as anxiety, depression, or other mental health problems, that include screening for COVID-19-related stressors and other stressful life events to prioritize the focus and locus of management.

Integration of telepsychiatry

Given the restrictions on in-person interactions, telehealth played a crucial role in providing continuous care. The center ensured that patients had access to telepsychiatry services, allowing them to receive treatment and support within the hospital and remotely.

Staff training and stress management

Staff was trained in how to recognize and respond to COVID-19-related mental health concerns as a part of an orientation program implemented in the hospital for every batch before posting in COVID ward duties. They were also supported with improving coping skills and management of their stress in adverse circumstances to ensure good self-care of staff.

Development of information, education, and communication (IEC) material

As most of people were faced with anxiety, depression, and various mental health concerns in the background of looming uncertainty during COVID-19, we developed IEC material covering common mental health problems, identification of symptoms and signs, strategies for managing pandemic-related anxiety, isolation, or grief at home and providing department counseling services and suicide helpline number.

Collaboration with Infection control team

Collaboration with the hospital infection control team to ensure safety protocols and infection control measures were rigorously followed to protect both patients and staff from COVID-19 exposure.

Evaluation and feedback

Continuously, we tried to evaluate the effectiveness of the experience-based treatment care model by collecting feedback from both patients and staff to make necessary improvements.

We tried to sail through all the hardships to give the best inpatient care by working on the safety of both the patients and staff, inter-departmental collaboration, patient and family education, IEC material, technology-integrated management options, and ongoing evaluation of the treatment care model. This model has utility and teachable moments for the post-COVID era as it provides a strong motive to transform experiences into practical insights particularly how telepsychiatry has undergone evolution. It also can aid in enhancing mental health care delivery, overall quality of care, and further in the prevention of future crises in COVID-like conditions and in the settings of limited resources.

CONCLUSION

The challenges brought by the COVID pandemic have led to a chain of changes in inpatient services provided by the psychiatry department. A successful experience-based treatment care model for inpatient psychiatry services during the COVID-19 crisis involves a holistic and evolving approach. It prioritizes safety, patient-centered care, and ongoing support, while leveraging technology and collaboration to address the unique challenges posed by the pandemic.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent is not required as patient’s identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Social inequity and access to mental healthcare in India during the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Humanit.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nondisrupted, safety ensured, opioid substitution clinic in a COVID-19 designated hospital of a resource-limited state in India. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2021;13:e12428.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fear, psychological impact, and coping during the initial phase of COVID-19 pandemic among the general population in India. Cureus. 2021;13:e20317.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- State of mental health services in various training centers in India during the lockdown and COVID-19 pandemic. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62:363-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- From asylums to bedless hospitals: Will COVID-19 catalyse a paradigm shift in psychiatry care in India? Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;54:102428.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental healthcare suffers as several Mumbai hospitals pull the plug on psychiatric admissions. The Indian Express. Available from: https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/mumbai/mental-healthcare-suffers-as-several-mumbai-hospitals-pull-the-plug-on-psychiatric-admissions-6498569/ [Last accessed on 2023 Jun 22]

- [Google Scholar]

- Status of healthcare workers in relation to COVID-19 infection: A retrospective study in a level 4 COVID hospital in eastern India. J Assoc Physicians India. 2020;68:55-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Should all patients admitted to hospitals be tested for COVID-19? The Wire Science. Available from: https://science.thewire.in/health/hospitals-covid-19-testing [Last accessed on 2023 Jun 22]

- [Google Scholar]