Translate this page into:

Presidential address: Ethics in Precision Psychiatry

*Corresponding author: Uttam C. Garg, Consultant Psychiatrist, Private Consultancy Clinic, Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India. uttamcgarg@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Garg UC. Presidential address: Ethics in Precision Psychiatry. Arch Biol Psychiatry 2023;1:41-5. doi: 10.25259/ABP_35_2023

Greetings Ladies and gentlemen esteemed psychiatrists and dignitaries. It is an honor for me to present my second presidential speech at the ANCIABP 2022. Today, I am going to discuss about a crucial topic in our ever-advancing field: Ethics in precision psychiatry. As we delve into an era of personalized medicine and tailored treatments, it is vital that we consider the ethical dimensions of these new approaches.

INTRODUCTION

Precision medicine is an approach that is therapeutic and preventive, and it enables healthcare providers to make clinical decisions based on specific individual characteristics.[1] The foundation of precision medicine lies in personalized clinical prediction models, which have various applications such as screening, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment planning.[2]

Psychiatry’s individualization is usually based on the clinical impression rather than the “objective” criteria that precision psychiatry can provide.[3,4] Precision psychiatry is gaining momentum and is expected to change especially when combined with preventive psychiatry but its transition into clinical practice is still in its early stages.

In addition, there is a need for a cogent ethical framework that everyone can agree on to guide future research and practice in this area.[3]

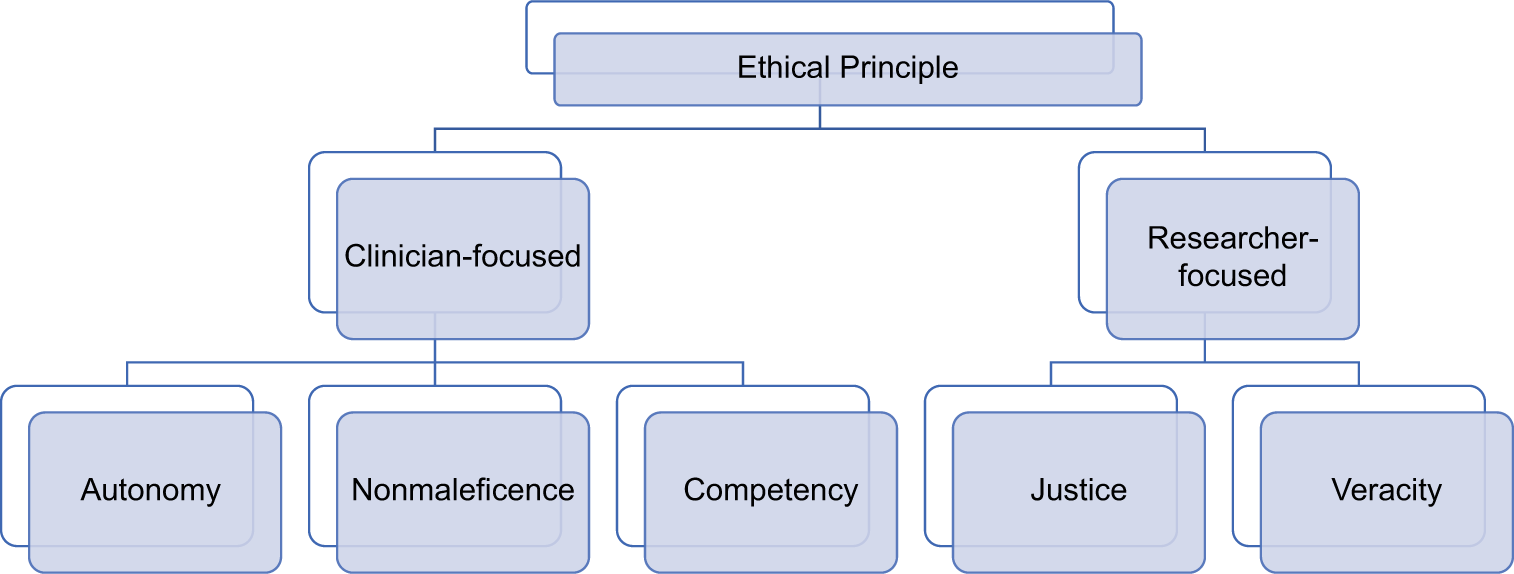

Key principles of precision psychiatry are divided into two categories[5] [Figure 1]:

-

For clinicians:

Autonomy

Non-maleficence

Competency

-

Researcher-oriented:

Justice

Veracity

- Key ethical principles.

AUTONOMY

Autonomy refers to the ability of individuals to make informed decisions about their mental health care based on personalized and precise information. Also known as self-determination, it involves empowering patients to actively participate in their unique genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors.[5] Autonomy extends beyond the informed consent process. When introducing routine and novel interventions or therapies, clinicians must ensure that patients and their caregivers are aware of the potential risks, benefits, and alternatives. This allows patients to actively participate in the decision-making process and make choices that align with their values and preferences.[3]

One such example is the use of genetic testing to guide treatment selection for psychiatric disorders. Genetic testing can provide valuable insights into an individual’s makeup and how they may respond to different medications.[6] By incorporating this, clinicians can help patients make more informed choices about which medications are likely to be most effective and have fewer side effects for them personally.[7]

Recent practice of autonomy lies in the use of digital health technologies, such as smartphone applications or wearable devices, to monitor and track mental health symptoms.[8] These technologies can provide individuals with real-time data about their own mental well-being, allowing them to actively participate in self-management and treatment planning. Patients can use this information to make informed decisions about when to seek additional support or ask for change in their treatment strategies.[9,10]

NONMALEFICENCE

Nonmaleficence, or the principle of “do no harm,” is a fundamental ethical principle in healthcare. In the context of precision psychiatry, it means tailoring treatments based on unique characteristics and understanding the balance between potential aid and harm that may occur.[5] Nonmaleficence can be applied in several ways, like being careful while considering the invasiveness and risk of harm from a procedure. When determining the most appropriate treatment approach, healthcare providers must weigh the potential benefits against the potential risks and adverse effects, that is, if a particular treatment option carries a high risk of severe side effects or complications, it may not be recommended for patients who are at a higher risk or have a poor prognosis. Another ethical concern is considering the severity and prognosis of the illness. For instance, for individuals with severe mental illnesses who have not responded well to standard treatments, more aggressive interventions may be considered, but only after carefully weighing the potential risks and benefits.[3]

Nonmaleficence also requires taking into account the psychosocial context of each patient. Mental health is influenced by various factors such as social support, living conditions, job, financial status, and cultural background. For example, the side effect of tremors in hands with antipsychotics has much more severe implications for a surgeon than a patient who works as a fruit seller.[3]

However, one should also remember that neglecting to implement effective precision methods in psychiatry could also harm the patients due to missed opportunities to do better.

COMPETENCY

Competency in precision psychiatry refers to the knowledge, skills, and abilities that mental health professionals need to effectively utilize and integrate precision-based approaches into their clinical practice. In simpler words, it means staying up to date with the latest advancements, understanding the complexities of precision medicine, and being able to interpret and apply precision-based information in a clinically meaningful way.[5]

One application of competency in precision psychiatry is the ability to interpret genetic or biomarker information accurately. The approaches often involve analyzing genetic variations or biomarkers to guide treatment decisions.[6,11,12] Another example is the competence to navigate and utilize digital health technologies effectively. As discussed earlier about digital tools such as smartphone applications, wearable devices, and online tools, clinicians should be competent and familiar with these transformative technologies, understand their limitations, and be able to interpret the data generated.[10,13,14] Psychiatrists need to be aware of the potential for false positives or false negatives in genetic testing, as well as the ethical considerations surrounding privacy and confidentiality when using digital health technologies.[15]

Furthermore, competency in precision psychiatry requires ongoing professional development and abreast of the latest research and advancements in the field. This includes attending conferences, participating in continuing education programs, and engaging in peer-reviewed literature to stay informed about emerging precision-based interventions and best practices.

JUSTICE

This ethical principle refers to the fair and equitable distribution of resources, benefits, and opportunities in mental healthcare. It involves addressing disparities and ensuring that all individuals, regardless of their background or circumstances, have equal access to personalized and precise mental health interventions.[5] It is the effort to reduce health disparities by increasing access to precision-based interventions for underserved populations.[16] This can be achieved by implementing strategies to reach individuals who may face barriers to accessing mental healthcare, such as those from low-income communities or marginalized groups. Precision psychiatry aims to ensure that everyone has an equal opportunity to benefit from advances in personalized treatment approaches, by the inclusion of diverse populations in research studies and clinical trials. Historically, certain groups have been under-represented in mental health research, leading to a lack of understanding about how different populations may respond to specific treatments. Precision psychiatry seeks to address this by actively recruiting participants from diverse backgrounds, including individuals with different ethnicities, socioeconomic statuses, and cultural backgrounds. In addition, justice in precision psychiatry involves considering the affordability and accessibility of precision-based interventions.

VERACITY

Veracity in precision psychiatry refers to the importance of truthfulness, honesty, and transparency in the field. It involves providing accurate and reliable information to patients, clinicians, and researchers, as well as promoting ethical conduct in the collection and interpretation of data.[5]

A way of practicing veracity is by transparent reporting of research findings, it is crucial for researchers to accurately report their methods, results, and any potential limitations or conflicts of interest. This ensures that the scientific community and clinicians have access to reliable information that can guide decision-making and inform clinical practice. Even when collecting and handling patient data for precision-based studies, researchers must adhere to strict ethical guidelines. Veracity also extends to the informed consent process. When discussing precision-based interventions with patients, clinicians must provide clear and accurate information about the risks, benefits, and uncertainties associated with these approaches.

By upholding veracity in precision psychiatry, trust is fostered between patients, clinicians, and researchers.

SO FAR THE ETHICAL IMPLICATIONS OF PRECISION PSYCHIATRY

Challenges and barriers

One of the main challenges in implementing precision psychiatry is the lack of standardized guidelines and protocols for data collection, analysis, and interpretation.[2,3] This can lead to inconsistencies in diagnosis and treatment recommendations, making it difficult to compare results across studies and populations. Another barrier is the limited availability of high-quality data, particularly in underrepresented groups and low-resource settings. In addition, there may be resistance from some stakeholders, such as patients, clinicians, and policymakers, who may be skeptical of the value and impact of precision psychiatry.[2,3]

Societal implications

The large-scale adoption of precision psychiatry has the potential to revolutionize mental healthcare, but it also raises several ethical questions. One of these concerns is the risk of increasing stigma and discrimination against people who are at high risk of developing mental health problems.[2,16] Another problem is the possibility of misuse of sensitive genetic and personal data. There is a risk that this information could be used for discriminatory purposes against people in areas such as employment, insurance, and access to healthcare. In addition, there are concerns that the introduction of precision psychiatry could exacerbate existing healthcare inequalities, as some populations may not have access to the necessary resources or may be reluctant to participate in genetic testing and analysis.

Enhancing the implementation of precision psychiatry

A recent comprehensive analysis discovered that under 1% of clinical prediction models published in the field of psychiatry were taken into consideration for real-world application in clinical settings.[3] This emphasizes significant gaps within the precision psychiatry translational process. It is crucial to address implementation obstacles during the initial stages of model development. Factors such as suboptimal accuracy, neurobiological interpretability, explainability, and generalizability have been shown to intensify the ethical barriers when applying precision psychiatry.[3,15,17]

Encouraging mental health literacy to strengthen collaboration between service users and healthcare providers:

Risk awareness, understanding of disease risk, and mental health literacy in critical contexts of risk-related actors are related to individual risk thresholds, how individuals deal with it, and how it translates into identity and health-related integrated behaviors. It plays an important role in understanding what can be integrated and their life plans. Promoting mental health literacy is therefore important for enhancing self-determination, autonomy, and collaboration among stakeholders. For example, community mental health services aimed at preventing psychosis offer mental health competency packs on susceptibility to psychosis and its impact on individuals as a family, thereby encouraging active collaboration between patients, their families, and physicians is supported. To address these issues in the future, research will need to carefully examine how precision models of psychiatry reconfigure interactions between patients, families, and providers.[3]

The solution

Engaging stakeholders is also crucial for overcoming barriers to precision psychiatry implementation, like those from diverse backgrounds and expertise, such as clinicians, researchers, data scientists, and patient advocates.[15] By working together, they can develop and implement standardized guidelines and protocols, ensure the availability and quality of data, and address any concerns or skepticism. In addition, interdisciplinary collaboration can facilitate the translation of research findings into clinical practice and policy, ultimately improving patient outcomes.[7] Overall, collaborators would feel more invested and empowered in the process, leading to greater buy-in and adoption of precision psychiatry.

CONCLUSION

Precision psychiatry is at the forefront of mental health innovations, but it also raises unprecedented ethical concerns at the individual, healthcare, and whole societal levels.

Ethical concerns regarding autonomy, nonmaleficence, competency, justice, and veracity have slowed the implementation of precision psychiatry into clinical practice.

While these concerns are valid and need to be carefully navigated, the risk of harm from slow or absent implementation is often overlooked.

By carefully considering and addressing ethical challenges, the implementation of precision psychiatry can advance more rapidly, with the goal of improving patient care and making the fruits of scientific research more equitably distributed.

As pioneers in this field, let us proceed with rigor, empathy, and commitment to ethical principles, paving the way for improved patient care for generations to come.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Dr. Kashypi Garg, Consultant Psychiatrist, Agra.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent was not required as there are no patients in this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The author(s) confirms that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Challenges and future prospects of precision medicine in psychiatry. Pharmgenomics Pers Med. 2020;13:127-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethical considerations for precision psychiatry: A roadmap for research and clinical practice. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022;63:17-34.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- "Precision psychiatry" needs to become part of “personalized psychiatry”. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2020;88:767-72.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethical implementation of precision psychiatry. Pers Med Psychiatry. 2020;19-20:100046.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The road to precision psychiatry: Translating genetics into disease mechanisms. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:1397-407.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Precision psychiatry in clinical practice. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2021;25:19-27.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A survey on wearable sensors for mental health monitoring. Sensors (Basel). 2023;23:1330.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Can precision medicine advance psychiatry? Ir J Psychol Med. 2021;38:163-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Precision psychiatry: The future is now. Can J Psychiatry. 2022;67:21-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Social science and medicine In: Major depressive disorder: Rethinking and understanding recent discoveries. Vol 1305. Germany: Springer Nature; 2021. p. :555.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Genetic testing for antipsychotic pharmacotherapy: Bench to bedside. Behav Sci (Basel). 2021;11:97.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethical perspectives on recommending digital technology for patients with mental illness. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2017;5:6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigendum to applications of machine learning algorithms to predict therapeutic outcomes in depression: A meta-analysis and systematic review. J Affect Disord 241 (2018) 519-532. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:1211-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Real-world implementation of precision psychiatry: A systematic review of barriers and facilitators. Brain Sci. 2022;12:934.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The ethical conundrums of “precision psychiatry”. Voices Bioeth. 2021;7:7-10.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The present and future of precision medicine in psychiatry: Focus on clinical psychopharmacology of antidepressants. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2018;16:1-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]