Translate this page into:

Metabolic syndrome in psychiatric disorders

*Corresponding author: Ashutosh Shah, Department of Psychiatry, Sir H N Reliance Foundation Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. ashutosh.shah@rfhospital.org

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Shah A. Metabolic syndrome in psychiatric disorders. Arch Biol Psychiatry. 2024;2:4-13. doi: 10.25259/ABP_24_2023

Abstract

Individuals suffering from psychiatric disorders are particularly vulnerable to early death, primarily from heart-related reasons. Patients with psychiatric disorders have a higher chance of developing metabolic syndrome. Numerous distinct cardiometabolic risk factors that raise morbidity and mortality are components of metabolic syndrome. There is a bidirectional longitudinal influence with metabolic syndrome and a correlation with the intensity and length of psychiatric symptoms. The development of metabolic syndrome is influenced by a number of factors, including an unhealthy diet, lack of sleep, alcoholism, smoking, genetic polymorphisms, mitochondrial dysfunction, immunometabolic and inflammatory conditions, endocrine abnormalities, and psychiatric medications. The elevated likelihood of metabolic syndrome in psychiatric disorders warrants extreme caution in preventing, closely observing, and managing individuals who are at risk.

Keywords

Metabolic syndrome

Mental disorders

Mortality

Obesity

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of obesity and severe mental illnesses (SMIs) has been increasing over the past three decades all over the world.[1,2] With limited financial and time resources, preventing non-communicable diseases is of utmost importance. Life expectancy is shortened by 7–24 years in people with SMIs. Cardiovascular diseases are responsible for around 60% of the mortality in people with SMIs. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome is 58% higher in people with SMIs compared to the general population. Metabolic syndrome predisposes the afflicted individual to cardiovascular disease and Type 2 diabetes mellitus.[3] Metabolic syndrome, therefore, should be prevented in patients with SMIs to avoid premature mortality and reduce morbidity.

METABOLIC SYNDROME

Haller and Hanefeld first coined the term metabolic syndrome in 1975.[4] Metabolic syndrome elevates the risk of developing Type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease and is a collection of interrelated physiological, biochemical, metabolic, and clinical risk factors. The core components of this syndrome are insulin resistance, central obesity, dyslipidemia, and arterial hypertension.[5] Several factors, including genetic, perinatal, dietary, and other lifestyle factors and age, determine vulnerability to Type 2 diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, and insulin resistance[6] [Figure 1]. Several expert groups have developed clinical criteria for metabolic syndrome; the most widely accepted criteria were produced by the World Health Organization, International Diabetes Federation (IDF), National Cholesterol Education and Program Third Adult Treatment Panel (NCEP ATP III), and the harmonization criteria for Asian Indians [Table 1]. Most definitions require the presence of at least three abnormal parameters for diagnosing metabolic syndrome.[7] The criteria by the IDF and NCEP ATP-III are easy to measure and require no lab tests. NCEP ATP-III is the most commonly used criteria set for defining metabolic syndrome.[8] NCEP ATP-III criteria require the presence of any three out of the five criteria for diagnosing metabolic syndrome. The IDF criteria require waist circumference as a mandatory criterion, plus two other criteria for diagnosing metabolic syndrome.[5] It is relevant to remember that each of the five distinct elements plays a significant role in risk assessment and acts as a separate risk factor for diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular illness, and coronary heart disease.[9] Several additional measurements are under research[5] [Table 2].

![Complex interactions between genetic, perinatal, nutritional, and other acquired factors in the development of insulin resistance, ischemic heart disease, and Type 2 diabetes mellitus in Asian Indian [Reproduced with permission from Dr P P Mohanan], PUFA : Polyunsaturated fatty acids.](/content/151/2024/2/1/img/ABP-2-004-g001.png)

- Complex interactions between genetic, perinatal, nutritional, and other acquired factors in the development of insulin resistance, ischemic heart disease, and Type 2 diabetes mellitus in Asian Indian [Reproduced with permission from Dr P P Mohanan], PUFA : Polyunsaturated fatty acids.

| S. No. | Risk factor | IDF | NCEP ATP III | Harmonization criterion for Asian Indians (Harmonization) | WHO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Abdominal obesity | ||||

| Men | Waist circumference based on ethnicity-specific values. | >102 cm | ≥90 cm | Waist/hip ratio >0.9 or BMI >30 kg/m2 |

|

| Women | >88 cm | ≥80 cm | Waist/hip ratio >0.85 or BMI >30 kg/m2 |

||

| 2. | HDL cholesterol | ||||

| Men | <40 mg/dL | <40 mg/dL | <40 mg/dL | <35 mg/dL | |

| Women | <50 mg/dL | <50 mg/dL | <50 mg/dL | <39 mg/dL | |

| 3. | Hypertriglyceridemia | ≥150 mg/dL | ≥150 mg/dL | ≥150 mg/dL | ≥150 mg/dL |

| or | |||||

| specific treatment for this lipid abnormality | |||||

| 4. | Hyperglycemia | ≥100 mg/dL or Previously diagnosed Type 2 diabetes |

≥110 mg/dL | ≥100 mg/dL | Impaired glucose tolerance or Type 2 diabetes or impaired fasting glucose |

| 5. | Blood pressure | Systolic>130 mm Hg or diastolic>85 mm Hg or on antihypertensive treatment |

Systolic >130 mm Hg or diastolic >85 mm Hg |

Systolic >130 mm Hg or diastolic >85 mm Hg |

≥140/90 mm Hg |

| 6. | Other | Microalbuminuria | |||

| Diagnostic criteria | Abdominal obesity plus any other two. | Any three out of the five. | Any three out of the five. | Type 2 diabetes mellitus plus any other two. |

IDF: International Diabetes Federation, NCEP ATP III: National Cholesterol Education Program’s Adult Treatment Panel III, WHO: World Health Organization, BMI: Body mass index, HDL: High-density lipoprotein

| Criteria | Tests |

|---|---|

| Abnormal body fat distribution | General body fat distribution (DEXA) Central fat distribution (CT/MRI) Adipose tissue biomarkers: leptin, adiponectin Liver fat content (MRS) |

| Atherogenic dyslipidemia (beyond elevated triglyceride and low HDL) |

ApoB (or non-HDL-C) Small LDL particles |

| Dysglycemia | OGTT |

| Insulin resistance | Fasting insulin/pro-insulin levels HOMA-IR insulin resistance by Bergman Minimal Model elevated free fatty acids (fasting and during OGTT) M value from clamp |

| Vascular dysregulation | Measurement of endothelial dysfunction microalbuminuria |

| Proinflammatory state | Elevated HsCRP Elevated inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6) Decrease in adiponectin plasma levels |

| Prothrombotic state | Fibrinolytic factors (PAI-1, etc.) Clotting factors (fibrinogen, etc.) |

| Hormonal factors | Pituitary adrenal axis |

CT: Computed tomography, MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging, MRS: Magnetic resonance spectroscopy, HOMA-IR: Homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance, OGTT: Oral glucose tolerance test, HsCRP: High-sensitivity C-reactive protein, TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha, IL-6: Interleukin-6, PAI-1: Plasminogen activator inhibitor Type 1, HDL-C: High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL: Low-density lipoprotein, DEXA: Dual Energy X-ray

It is estimated that around 20–25% of the population worldwide has metabolic syndrome.[9] A two-fold increase in death risk, a three-fold increase in heart attack or stroke risk, and a five-fold rise in Type 2 diabetes mellitus risk are linked to metabolic syndrome.[5] The individuals’ financial, emotional, and psychosocial well-being is significantly impacted by metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome increases the risk of developing psychiatric disorders like major depressive disorder, which would then further reduce the quality of life for the afflicted person.[9] Individuals with SMIs have a two to three-times increased risk of developing metabolic syndrome.[9]

Nationally representative studies are generally not available in any South Asian country. About 33% of the population residing in Indian cities are estimated to have metabolic syndrome. Significant differences exist within different urban socioeconomic groups with regard to the prevalence of metabolic syndrome. While both genders are at equal risk for metabolic syndrome, after the age of 70 years, there is an increased prevalence in females. Males and females in the age group of 40–59 years were three times more likely to have metabolic syndrome compared with the age group of 20–39 years.[6]

METABOLIC SYNDROME IN PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

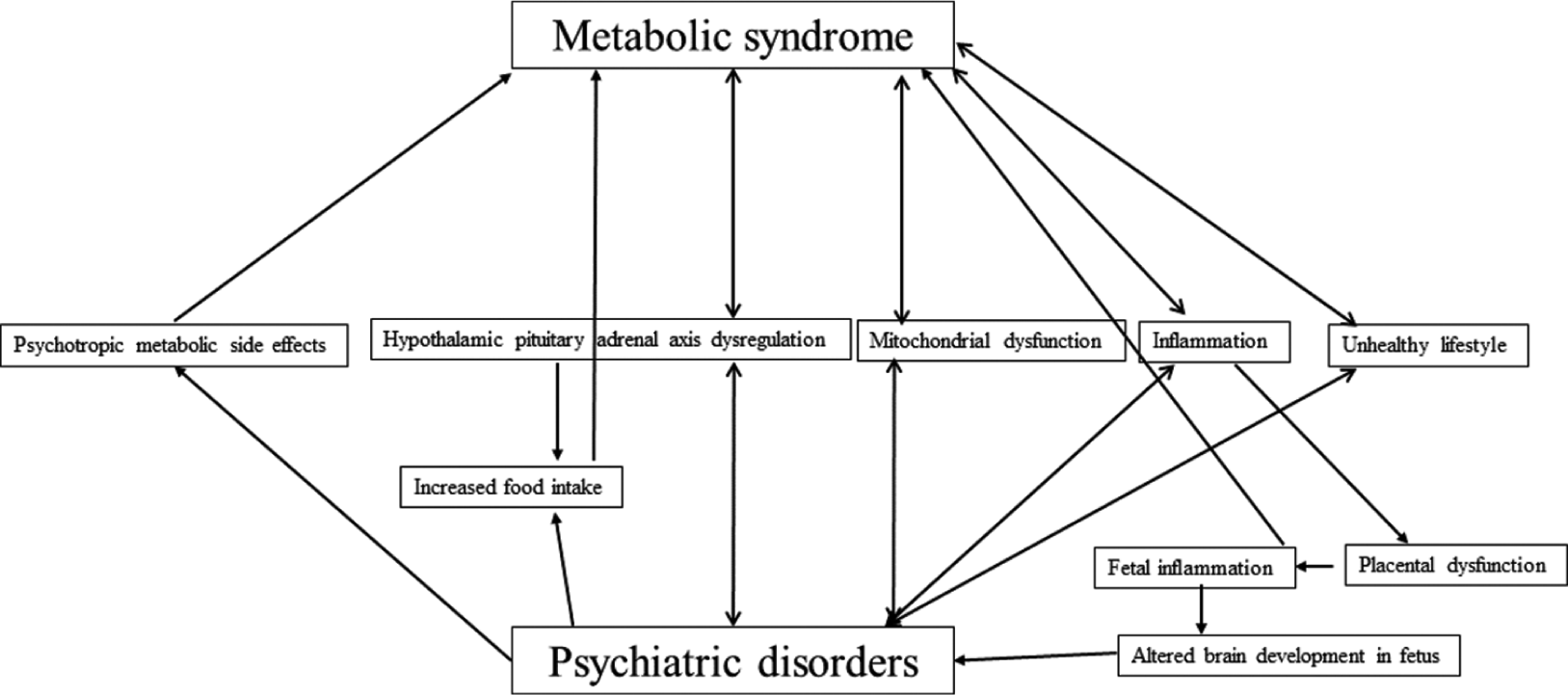

The typical metabolic syndrome risk factors in chronic psychiatric illnesses are tabulated in Table 3. Multiple mechanisms are proposed for the bidirectional association between metabolic syndrome and psychiatric disorders[10] [Figure 2].

|

- Common mechanisms and bidirectional relationship between metabolic syndrome and psychiatric disorders.

PSYCHOSIS (SCHIZOPHRENIA AND BIPOLAR DISORDER)

The estimated prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients suffering from schizophrenia varies from 8.9% to 68%.[9] The prevalence rate of metabolic syndrome in Indian patients suffering from schizophrenia is comparable to that reported in Western world studies.[11]

Individuals suffering from schizophrenia have a two-to–three-fold higher risk of mortality compared to the general population. Cardiovascular diseases are the main cause of death in individuals suffering from schizophrenia.[12] The risk of developing metabolic syndrome is five times higher in patients with schizophrenia as compared with the general population.[9] Individuals suffering from schizophrenia are at greater odds of having abdominal obesity (odds ratio [OR] = 4.43), hypertriglyceridemia (OR = 2.73), low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (OR = 2.35), metabolic syndrome (OR = 2.35), and hypertension (OR = 1.36).[13] Individuals with schizophrenia who are female are more likely to acquire metabolic syndrome.[14] Patients suffering from schizoaffective disorder have a slightly greater risk of developing metabolic syndrome compared to patients suffering from schizophrenia.[15]

The prevalence of Type 2 diabetes mellitus is two to three times higher in patients suffering from schizophrenia compared with the general population.[16] This increased prevalence is independent of antipsychotic use. Antipsychotic-naïve schizophrenia patients exhibited greater intra-abdominal fat deposition, poorer glucose tolerance, and higher insulin resistance in comparison to normal controls.[17] The glucose tolerance of schizophrenia patients’ siblings was compromised.[18] Parents of those with non-affective psychosis were more likely to have Type 2 diabetes mellitus.[19] It is suggested that metabolic imbalance is a fundamental feature of schizophrenia.[9]

Genetic factors, immune, metabolic, and endocrine factors, lifestyle factors, and antipsychotic-induced weight gain are the various mechanisms by which metabolic syndrome could develop in patients with schizophrenia.

In schizophrenia, genetic factors may play a role in the development of metabolic syndrome. Several genes have shown a strong correlation between metabolic syndrome in schizophrenia: LEP, MTHFR, BDNF, LEPR, HTR2C, and FTO. There is a complex genetic relationship between metabolic syndrome and schizophrenia. Mechanisms other than disease-specific genetics play a pivotal role in the development of metabolic disturbances in patients with schizophrenia.[20]

Chronic subclinical inflammation occurs in metabolic syndrome. In metabolic syndrome, there are changes in C-reactive protein (CRP), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), leptin, and adiponectin levels.[21] Lipid, glucose, and energy homeostasis are regulated by adiponectin and leptin. As obesity increases, the level of adiponectin decreases. Adiponectin is anti-atherogenic and has a good correlation with insulin sensitivity. Because leptin increases the synthesis of IL-6 and TNF-α, it reduces the effectiveness of insulin and increases inflammation. There is mounting evidence that inflammation has a role in the development of metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia. Comorbidity of obesity with schizophrenia is associated with reduced adiponectin and increased levels of leptin, TNF-α, and IL-6, which increases the risk of atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease.[9] Serum homocysteine, CRP, and TNF-α levels are higher in schizophrenia patients.[22] Diastolic blood pressure and waist circumference have been directly correlated with CRP. Blood pressure, lipids, blood glucose, and waist circumference have all been positively correlated with homocysteine.[23] During a 12-week trial, individuals with aberrant baseline IL-6 levels experienced higher rises in their total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels when treated with olanzapine.[24] A risk factor for metabolic syndrome was the total white blood cell count, which is a proxy indicator of inflammation, in another study that involved a 24-week course of paliperidone treatment. The study found a positive correlation between an increase in blood glucose levels and waist circumference and the total white blood cell count.[25]

Lifestyle factors that predispose patients of schizophrenia to metabolic syndrome include inactive lifestyle, poor dietary choices, poor sleep hygiene, excessive alcohol consumption, and smoking nicotine.[8,25] These lifestyle characteristics include impaired insight, negative symptoms of schizophrenia, and medication-induced drowsiness.[9] There is also less likelihood that patients with schizophrenia would receive the standard or optimal level of medical care.[26-28]

Other reasons for metabolic syndrome in persons with schizophrenia include antipsychotics and antipsychotic-induced weight gain. Strong data suggests that antipsychotic medication lowers hospital admissions, suicide rates, and morbidity.[29,30] The ranking of Second Generation Antipsychotics (SGAs) according to decreasing relative risk of developing metabolic syndrome is as follows: clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, aripiprazole, and ziprasidone.[31] According to the NCEP-ATP III criteria, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with first-episode schizophrenia on antipsychotic treatment is estimated to be approximately 10%, and according to IDF criteria, it is approximately 18%.[32] Antagonism of the 5HT2C receptor increases the risk of Type II diabetes mellitus by causing insulin resistance and decreased skeletal muscle absorption of glucose. Blockade of H1 and H3 receptors lead to reduction in metabolism as histamine receptors mediate energy intake and expenditure.[9] Several pre-clinical and clinical studies have demonstrated that glucose dysregulation occurs within minutes to hours following antipsychotic treatment, even in the absence of weight gain.[33] Twin studies imply that 5-HT2C receptor polymorphism may play a role in the genetic variability associated with weight gain induced by antipsychotics. There have also been genetic differences linked to the satiety pathways. Through the melanocortin system (α-melanocyte stimulating hormone and agouti-related peptide) and neuropeptide Y, the leptin system controls hunger and energy metabolism.[9] A higher risk of developing metabolic syndrome is linked to polymorphisms in the leptin receptor gene LEPR and the leptin gene LEP. Antipsychotic polypharmacy increases the risk of developing metabolic syndrome. The incidence of metabolic syndrome in antipsychotic polypharmacy was 50% versus 30% in antipsychotic monotherapy in one study.[34] The combination of aripiprazole with clozapine has been advocated to be beneficial by reducing lipid levels.[35]

The estimated prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients suffering from bipolar disorder varies between 16.7% and 67%.[8] Many factors, such as hypothalamic–pituitary– adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulation, impaired glucose tolerance and insulin resistance, increased pro-inflammatory cytokine production, unhealthy lifestyle, and mitochondrial dysfunction during both phases of bipolar disorder are implicated in causing metabolic syndrome in bipolar disorder patients.[9,36] The clinical risk factors associated with developing metabolic syndrome in bipolar disorder patients are shown in Table 4.[8]

|

Metabolic syndrome affects the course of bipolar disorder. Individuals with bipolar illness who also have Type 2 diabetes mellitus have a higher chance of suffering rapid cycling, decreased functioning, and more psychiatric hospitalizations than individuals without this comorbidity.[9] There have also been reports of high lifetime suicide attempt rates among comorbid bipolar disorder and metabolic syndrome patients.[37] Mood stabilizers, particularly sodium valproate and lithium, have been associated with metabolic syndrome.[38] Administering either mood stabilizers with antipsychotics or combining mood stabilizers increases the odds of developing metabolic syndrome.[38]

MAJOR DEPRESSIVE DISORDERS

The estimated prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients suffering from major depressive disorders (depression) ranges from 36% to 50%.[9] A systematic review involving over a hundred and fifty thousand subjects from 29 studies found depression and metabolic syndrome were modestly associated with an adjusted OR of 1.34.[39] Depression and metabolic syndrome appear to be associated in a dose– response manner, that is, the higher the severity of depression, the greater the risk of developing metabolic syndrome.[40] According to the scant prospective data currently available, there is a reciprocal association between depression and metabolic syndrome, meaning that depression predicts the onset of metabolic syndrome and vice versa over time.[39] Brain energy metabolism disruption due to mitochondrial dysfunction is a proposed mechanism linking both metabolic syndrome and psychiatric disorders like depression.[36] There is evidence linking depression to hypertriglyceridemia, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and abdominal obesity.[41] Less often are associations with hypertension and hyperglycemia verified. Comorbid depression and metabolic syndrome contribute to the patient remaining in a depressed state. Patients with metabolic syndrome are less likely to experience affective and cognitive symptoms of depression; instead, neurovegetative symptoms such as anhedonia, exhaustion, and loss of energy predominate.[3] Factors involved in the development of metabolic syndrome in depression are shown in Table 5.[9] Metabolic syndrome risk is higher in patients using antidepressants such as paroxetine, amitriptyline, and mirtazapine, which are linked to short-term weight gain.[3,42]

|

HPA: Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal, VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor

COGNITIVE DECLINE AND DEMENTIA

Cognitive impairment is more likely to occur in the elderly with metabolic syndrome than in the elderly without metabolic syndrome.[43] Deficits in different aspects of cognition are linked to metabolic syndrome.[44] It is suspected that many processes, including neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, poor glucose metabolism, and reduced vascular responsiveness, influence brain functioning in individuals with metabolic syndrome.[9] Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-1β are overproduced in metabolic syndrome. These cytokines promote the overexpression of the amyloid-β precursor protein, which results in an excess of amyloid-β deposits in the brain. In a vicious cycle, this amyloid-β accumulation raises cytokine production even more. Excess production of cytokines also accelerates atherosclerosis and increases the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.[45] Carotid stiffness increases along with the thickening of intima-media in metabolic syndrome. This leads to reductions in blood flow to the cerebral cortex, impairing nutrient supply and metabolic waste removal. Disruption of neuronal functioning occurs, possibly causing cognitive decline.[9]

OTHER PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) patients was 38.7% in one meta-analysis. Metabolic syndrome was 1.82 times more common in patients with PTSD, and this risk remained constant across geographic locations and independent of the presence or absence of war veteran status.[3] PTSD is associated with cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity, hypertension, and Type 2 diabetes mellitus.[46] Metabolic syndrome risk is higher in those with severe and persistent PTSD. Dysregulation of glucose and lipid metabolism occurring secondary to HPA axis disturbances in PTSD patients may contribute to the development of metabolic syndrome.[9]

50–60% of obese patients with binge eating disorder have metabolic syndrome. The most likely contributing variables are increased dyslipidemias, poor glucose tolerance tests, impaired fasting glucose, and excess insulin secretion.[47]

Borderline personality disorder patients have double the risk of having metabolic syndrome compared to patients in primary care. Older age, higher body mass index, use of SGAs, benzodiazepine dependence, dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary system, and binge eating behaviors are the associated factors.[48]

Abuse of alcohol disrupts the metabolism of fat and carbohydrates, raising the risk of abdominal obesity, hypertension, impaired fasting glucose, and hypertriglyceridemia. Alcohol depletes the body’s nutrients and harms all of its organ systems. Alcohol dependence is highly comorbid with other psychiatric disorders such as depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, or personality disorders. These disorders additionally elevate the risk of metabolic syndrome in alcohol use disorder patients.[9]

A study discovered that children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) had a higher risk (OR = 1.85) of obesity and problems connected to obesity. Patients with ASD are more likely to develop metabolic syndrome as a result of long-term usage of various psychotropics.[49]

The relationship between children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and metabolic syndrome has received very little research. A small number of adult findings suggest that lipid profile changes and an increase in body mass index may be associated with ADHD. However, these results are contradictory, and there are not enough well-powered research.[50]

PREVENTION AND TREATMENT OF METABOLIC SYNDROME

By now, the reader would be aware that individuals with psychiatric disorders are at high risk for developing metabolic syndrome. This calls for increased vigilance by the treating psychiatrist for the prevention and early detection of metabolic syndrome. Several studies have shown that somatic comorbidities are underdiagnosed and undertreated in individuals with psychiatric disorders.[51-52] Prevention strategies include:

At the baseline visit, a thorough anamnesis included family medical history and clinical examination. Thereafter, maintaining vigilance and clinical examination at periodic time intervals [Table 6]. Simple clinical measures such as measuring waist circumference and blood pressure would be cost-effective and more useful from a prevention and monitoring perspective of metabolic syndrome.[8]

Educating the patient about their higher risk for developing metabolic syndrome.

Recommending lifestyle modifications for every patient: Healthy food intake, adequate physical activity, good sleep, and discontinuing alcohol and smoking. A detailed review of each of these lifestyle modifications is out of the scope of this review, and the reader is referred to excellent sources on each of these.[53-57]

Awareness of the metabolic risk profile of the psychotropics prescribed. Prescription of psychotropic with reduced metabolic impact as far as feasible and personalized medication as per the clinically identified metabolic syndrome risk factors.

Aggressively tackle weight gain and/or obesity in liaison with other medical specialists. Detailed review of measures to tackle weight gain and combat obesity are out of the scope of this review and the reader is referred to an excellent source on this topic.[58-60]

Once metabolic syndrome or its complications are identified, liaison with medical specialists is recommended.

| Baseline visit | Week 6 visit | Week 12 visit | Week 52 visit | Annually after week 52 visit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical history | ☑ | ||||

| Lifestyle history* | ☑ | ||||

| Alcohol/smoking history | ☑ | ||||

| Family history@ | ☑ | ||||

| Height, weight and BMI | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ |

| Waist circumference | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ |

| Blood pressure | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ |

| Fasting plasma glucose | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ |

| Lipid profile | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ |

| Liver function tests | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ |

| Choice of psychotropics | ☑ | ||||

| Educating patient$ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ |

| Referral to medical specialists | If metabolic syndrome criteria are fulfilled | ||||

| Monitor alcohol/smoking use | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | |

| Review choice of psychotropics% | ☑ | ||||

CONCLUSION

Patients with psychiatric disorders are at a higher risk for metabolic syndrome. There is a bidirectional relationship between psychiatric disorders and metabolic syndrome. Prevention and early identification of metabolic syndrome in patients with psychiatric disorders is within the scope of psychiatrists’ competence. Liaison with medical specialists to treat metabolic syndrome not only reduces the risks of somatic illnesses but also helps improve the primary psychiatric disorder.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient consent is not required as there are no patients in this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128•9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390:2627-42.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9:137-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic syndrome in psychiatric patients: Overview, mechanisms, and implications. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20:63-73.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Synoptische Betrachtung metabolischer risikofaktoren In: Haller H. Hanefeld M, Jaross W, editors. Lipidstoffwechselstörungen. Jena: Gustav Fischer Verlag; 1975. p. :254-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic syndrome-a new world-wide definition. A Consensus Statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med. 2006;23:469-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic syndrome in the Indian population: Public health implications. Hypertens J. 2016;2:1-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109:433-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic syndrome in bipolar disorder. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34:110-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic syndrome in psychiatry: Advances in understanding and management. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2014;20:101-12.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Unraveling the mechanisms responsible for the comorbidity between metabolic syndrome and mental health disorders. Neuroendocrinology. 2013;98:254-66.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and determinants of metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of Indian studies. Asian J Psychiatry. 2016;22:86-92.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence and predictive value of individual criteria for metabolic syndrome in schizophrenia: A Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort Study. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11:262-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A meta-analysis of cardio-metabolic abnormalities in drug naïve, first-episode and multi-episode patients with schizophrenia versus general population controls. World Psychiatry. 2013;12:240-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: Baseline results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III. Schizophr Res. 2005;80:19-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schizoaffective disorder and metabolic syndrome: A meta-analytic comparison with schizophrenia and other non-affective psychoses. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;66-7:127-34.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardiovascular disease and diabetes in people with severe mental illness position statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Psychiatry J Assoc Eur Psychiatr. 2009;24:412-24.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interventions for the metabolic syndrome in schizophrenia: A review. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2012;3:141-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glucose abnormalities in the siblings of people with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;103:110-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parental history of Type 2 diabetes in patients with nonaffective psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2008;98:302-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Identification of genetic loci that overlap between schizophrenia and metabolic syndrome. Psychiatry Res. 2022;318:114947.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic syndrome: Updates on pathophysiology and management in 2021. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:786.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Similar immune profile in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: selective increase in soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor I and von Willebrand factor. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11:726-34.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association between C-reactive protein and homocysteine with the subcomponents of metabolic syndrome in stable patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Nord J Psychiatry. 2013;67:320-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic effects of olanzapine in patients with newly diagnosed psychosis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31:154-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relationship between inflammation and metabolic syndrome following treatment with paliperidone for schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;39:295-300.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifestyle factors and the metabolic syndrome in Schizophrenia: A cross-sectional study. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2017;16:12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Physical health care of patients with schizophrenia in primary care: A comparative study. Fam Pract. 2006;24:34-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Increasing global burden of cardiovascular disease in general populations and patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(Suppl 4):4-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long-term effects of antipsychotics on mortality in patients with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Psychiatry. 2022;44:664-73.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maintenance treatment with antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: A cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2022;48:738-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Second-generation (Atypical) antipsychotics and metabolic effects: A comprehensive literature review. CNS Drugs. 2005;19(Supplement 1):1-93.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic syndrome in first episode schizophrenia-a randomized double-blind controlled, short-term prospective study. Schizophr Res. 2008;101:266-72.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peripheral mechanisms of acute olanzapine induced metabolic dysfunction: A review of in vivo models and treatment approaches. Behav Brain Res. 2021;400:113049.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Does antipsychotic polypharmacy increase the risk for metabolic syndrome? Schizophr Res. 2007;89:91-100.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of adjunctive treatment with aripiprazole on body weight and clinical efficacy in schizophrenia patients treated with clozapine: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13:1115-25.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitochondrial genetics in mental disorders: The bioenergy viewpoint. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2023;67:80-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic syndrome in bipolar disorder: findings from the Bipolar Disorder Center for Pennsylvanians. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:424-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of metabolic disturbances in patients with bipolar disorder in Taiwan. J Affect Disord. 2009;117:124-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidirectional association between depression and metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1171-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic syndrome abnormalities are associated with severity of anxiety and depression and with tricyclic antidepressant use. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122:30-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depression and cardiovascular disease: Epidemiological evidence on their linking mechanisms. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;74:277-86.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic disorders induced by psychotropic drugs. Ann Endocrinol. 2023;84:357-63.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The metabolic syndrome, inflammation, and risk of cognitive decline. JAMA. 2004;292:2237-42.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of metabolic syndrome on cognition and brain: A selected review of the literature. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:2060-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The vascular hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: A key to preclinical prediction of dementia using neuroimaging. J Alzheimers Dis JAD. 2018;63:35-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic syndrome: Relative risk associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) severity and antipsychotic medication use. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:550-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The challenges of metabolic syndrome in eating disorders. Psychiatr Ann. 2020;50:346-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with borderline personality disorder: Results from a cross-sectional study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;263:205-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autism spectrum disorders and metabolic complications of obesity. J Pediatr. 2016;178:183-7.e1.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The association between metabolic syndrome, obesity-related outcomes, and ADHD in adults with comorbid affective disorders. J Atten Disord. 2018;22:460-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undiagnosed cardiovascular disease prior to cardiovascular death in individuals with severe mental illness. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019;139:558-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barriers to somatic health care for persons with severe mental illness in Belgium: A qualitative study of patients' and healthcare professionals' perspectives. Front Psychiatry. 2022;12:798530.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:1451-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Years of life gained when meeting sleep duration recommendations in Canada. Sleep Med. 2022;100:85-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benefits of adhering to sleep duration recommendations: Reframing an enduring issue. Sleep Med. 2023;101:373-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietary factors and risks of cardiovascular diseases: An umbrella review. Nutrients. 2020;12:1088.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diet and exercise in the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:545-55.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifestyle behaviors, metabolic disturbances, and weight gain in psychiatric inpatients treated with weight gain-associated medication. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2022;273:839-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metformin in the management of antipsychotic-induced weight gain in adults with psychosis: Development of the first evidence-based guideline using GRADE methodology. Evid Based Ment Health. 2022;25:15-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pharmacotherapy of obesity: An update on the available medications and drugs under investigation. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;58:101882.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]